How can small (and large) water systems pay for energy efficiency and renewable energy, helping cut energy costs? As energy is often the largest variable expense in a water system’s operating budget, this is a recurring question for the ongoing Smart Management for Small Water Systems project. There are many answers on how to pay for energy improvements, such as in my previous blog post on energy savings performance contracting, and throughout the Environmental Finance Center’s clean energy finance work. One such financing mechanism which water systems could employ is the Internal Energy Revolving Fund. How do these funds work?

The Internal Energy Revolving Fund Concept

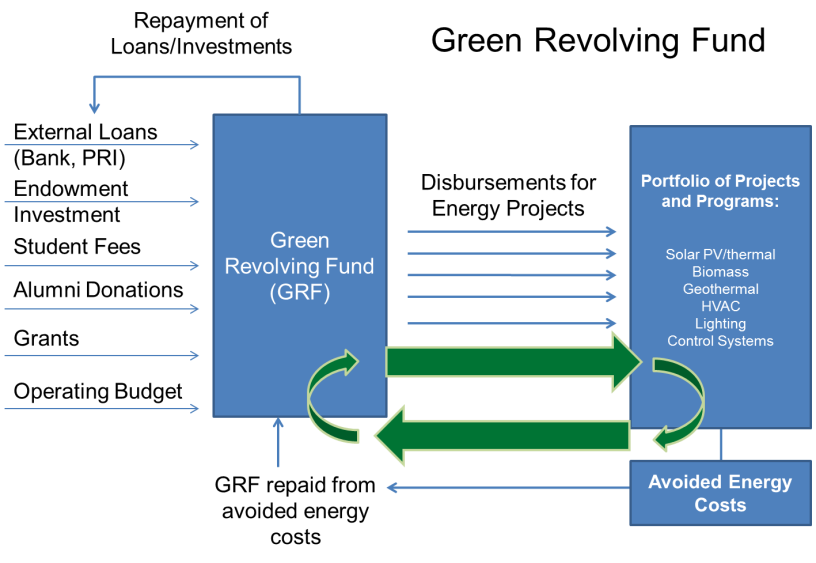

An Internal Energy Revolving Fund (IERF), also known as an “Energy Bank” or “Green Revolving Fund,” is a fund that is “internal” to an organization (e.g. a water system), where the fund pays for energy improvements for units within that organization to finance clean energy projects (e.g. pumps and motors, lighting, HVAC equipment, solar panels, etc.), and the fund “revolves.” Internal expenditures by the fund for energy improvements are repaid to the fund from the avoided energy costs from these measures. An initial investment (seed money) is needed to capitalize the fund. And once the fund is recapitalized by these repayments, additional such energy projects can be financed – thus a “virtuous cycle” is established for long-term success. Essentially, you have your own energy bank within your organization, from which departments can borrow to fund clean energy projects.

The Internal Energy Revolving Fund concept has been used by a number of local governments in North Carolina and around the country. The Town of Chapel Hill, N.C. set up an “Energy Bank” in 2003 with a $500,000 municipal bond referendum, and numerous projects to avoid energy costs have been funded, such as replacing a nearly 20-year old HVAC system at Town Hall, and paying for a new digital energy management control system. Union County, N.C., used American Recovery and Reinvestment Act grant funds starting in 2009 to establish a “Revolving Energy Fund,” funding lighting, HVAC, and solar thermal projects expected to avoid $210,000 annually in energy costs. And the city of Ann Arbor, Michigan, established a “Municipal Energy Fund” in 1998 to pay for lighting improvements, LED traffic signals, solar photovoltaic panels, etc. – the city reports that, annually, more than 1,000 MW of electricity has been avoided, as well as 270 MCF of natural gas, and 180 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions were reduced.

Though colleges and universities operate in substantially different ways from local governments and water utilities, it still bears noting that many U.S. institutions of higher learning have employed the Internal Energy Revolving Fund approach as well. Over 80 U.S. colleges and universities now have Green Revolving Funds, a subject explored on our blog here. For example, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, two such funds have been established, both the university’s Green Revolving Fund (GRF), and the Renewable Energy Special Projects Committee Revolving Fund, run by dedicated UNC students. One GRF-funded project has been to outfit a campus building with LED lighting, avoiding $1,000,000 in energy and maintenance costs across 20 years, with less than a 3 year simple payback period. Similarly, Harvard University’s Green Revolving Fund has a $12 million fund which has supported nearly 200 projects, yielding $4 million in avoided energy costs annually. Now let us look at what are some of the chief pros and cons of this approach.

Setting up an Internal Energy Revolving Fund

There are a number of questions to consider when first setting up an Internal Energy Revolving Fund, including (but not limited to) the following. Has an energy assessment been done first, to establish the energy usage baseline? Even if so, has a clear basis been established for repayments to the fund? For example, the actual avoided energy costs could be carefully monitored and verified (M&V). Or, since this may be arduous in practice, estimated avoided energy costs could be used instead. Also, a set annual appropriation back to the fund may be used.

As for the pace of repayments, will 100% of the avoided energy costs per unit of time (e.g. monthly) be repaid to the fund right away, or less than 100%, or more than 100%? For example, will some of the avoided energy costs be used to pay for the administrative overhead of the fund – an argument for repaying less than 100% of avoided energy costs per month/quarter/year?

Additionally, water systems that are owned by local governments may be subject to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, including best practices for Enterprise Funds (e.g. for drinking water) to be run largely financially independently from the General Fund. Thus if a town has an existing Internal Energy Revolving Fund for the General Fund, it may not be advisable or possible to simply expand it into the water system’s operations – a separate Internal Energy Revolving Fund may need to be set up.

Advantages and Opportunities

Establishing an Internal Energy Revolving Fund can have several advantages. First, it allows your organization to provide a continual stream of funds for energy improvements without tapping into existing capital cycles. In other words, if you have sufficient funds in your Internal Energy Revolving Fund, you may be able to finance energy management projects just from that source, without having to apply for loans or grants externally, or seeking funding through the water system’s existing overall capital budget.

This, in turn, may lead to simpler project management, at least in terms of the funding source and its associated application and reporting requirements – but this will depend upon the circumstances (see below for potential downsides).

Also, you may be able to combine this clean energy funding mechanism with others. For example, for an external grant to finance energy projects, instead of spending the funds on a once-only project, you could use the grant as seed money for a new Internal Energy Revolving Fund – or to increase an existing one.

Key Challenges

There are some key challenges that may arise when using this funding model. First, do you have a way to initially capitalize the fund, and at a scale large enough to fund significant energy management projects? You can always start small and “work your way up.” But finding a sizeable grant application for seed money, issuing a bond referendum, seeking inclusion in the water system’s existing capital improvement fund processes, etc., may prove challenging.

Second, will your intended energy projects fit within a time frame supportable by the fund? Some energy projects may be more suitable in size and duration for an Internal Energy Revolving Fund (e.g. those that take 5 to 10 years or less to repay). Other projects (e.g. ones with significantly longer simple payback periods) may need to funded in some other way, such as being rolled into a bundle of energy projects funded through an Energy Savings Performance Contract. Note that the Town of Chapel Hill has a seven year maximum simple payback period.

Third, has the administrative management to track the performance of the Internal Energy Revolving Fund, take funding applications, process repayments, etc., been adequately staffed and planned for? How will this administrative overhead be paid for, out of what funding source? Has the structure of, and procedures for, the fund been clearly laid out in writing, to help protect against confusion, or temptation (e.g. to “raid the fund” for purposes other than energy management), or generally to keep everyone in the organization clear as to why certain units are receiving funding, and for what purposes?

Finally, the governing body to whom the Internal Energy Revolving Fund is accountable (e.g. a Town Board, a Board of County Commissioners, etc.) may set out reporting requirements for the duration of the project funding for which you must plan. A good illustration of this comes from Chapel Hill, for quarterly reports by staff to the Town Board, including elements such as:

- Avoided expenses in Kwh of electricity, CCF of natural gas, or gallons of water

- Avoided costs in dollars (including normalizing for utility rate changes)

- Weather normalization using heating/cooling degree day data for the period covered

Not every governing board may require all such reporting elements. And this may still be easier and less time consuming than reporting requirements for an external funding agency (e.g. a bank or a state/federal agency).

Despite the cautions above, all energy financing mechanisms have their trade-offs. Internal Energy Revolving Funds are a way of financing projects to avoid energy costs for water systems, promoting a virtuous cycle of clean energy work in the drinking water sector.

Leave a Reply