Guest Post by Lars Hanson

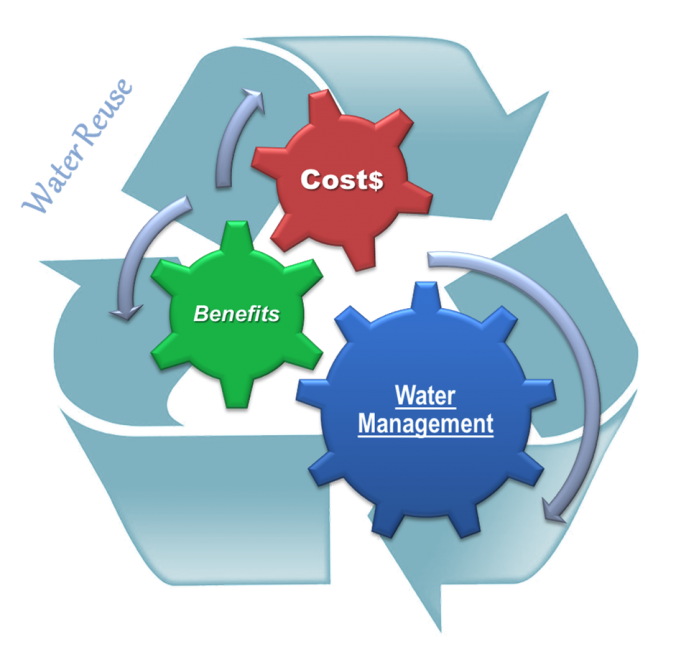

For utilities across the country, water reuse has been attracting a great deal of attention recently, and with good reason. As utilities and the communities they serve grow and mature, they find themselves managing increasing pressures relating to water availability, competition, customer service needs, and evolving regulations. These pressures require the Water Resources Utility of the Future to begin paying more attention to the interrelated nature of the core water management functions, including water supply and treatment, wastewater collection and treatment, stormwater management, and flooding and flow management. In addition to more coordinated planning, new ways of managing water will be needed to coordinate these functions. Water reuse is one water management tool that allows linking these functions, while also potentially providing a financial return when reclaimed water is sold.

But what is water reuse anyway? Water reuse, often referred to as water recycling or water reclamation (and hopefully not ‘toilet-to-tap’), is a general term referring to the treatment of a ‘used’ water source followed by subsequent beneficial use. Simple enough, but that definition perhaps oversimplifies the huge range of water reuse system concepts, and why water reuse projects are built.

There’s no single agreed-upon view of what a water reuse system looks like as concept, or what the motivations are. Is it a separate type of utility service that supplies a particular good (treated, purified, reclaimed water) to customers with a demand for it? Is it a way for an existing utility to improve cost-recovery by selling a resource that would otherwise be discharged? Is it a way to meet regional or local needs for water supply, or reliability? Or is it a water management tool to help comply with regulations as diverse as wastewater effluent loading limits, nutrient management strategies, or interbasin transfer rules?

There’s no wrong answer. In many cases, it’s a combination of these factors. But the way in which utilities view water reuse projects significantly shapes how they evaluate the potential costs and benefits, and ultimately, the likelihood of implementing a project.

Water reuse projects have seen enormous growth over the past several years, but they have been uneven across the country. California, Florida, Texas and Arizona have made substantial progress in implementing water reuse projects in part due to pressing needs for water supply, and in part due to availability of regulatory support and financing. But acceptance across the country has been uneven, so it’s worth examining why that has been the case.

The role of cost and other factors in water reuse decision making

The decision to build a water reuse system (or not build one) is influenced by multiple potential drivers, objectives, and hindrances.

At some level, an economically rational utility would decide to build water reuse projects when projected benefits exceed costs; when there is some certainty that the project can recover costs through additional revenue. Judged in these terms, water reuse projects start out at a disadvantage compared to traditional water supply and treatment projects simply because they require expensive new infrastructure and additional operational capabilities. The relatively high costs of the required infrastructure (especially the distribution infrastructure) have been identified as major barriers to implementation of water reuse.

Is the key to water reuse project implementation simply finding the point at which the projected benefits (revenues) exceed projected costs? Optimizing the system size to maximize customers served with minimum distribution infrastructure?

A strict financial analysis – one only concerned with the projected, quantifiable, monetary impacts – may not be sufficient to capture the potential benefits of a water reuse project. There are numerous potential drivers for water reuse projects that provide indirect or non-financial benefits. Many of these benefits may not even accrue to the utility or project proponent. For example, the EFC’s recent project in Arizona found the water reuse projects could be a win-win-win with benefits accruing to customers, the utility, and the community.

As with all questions concerning water resources management, location – including climate and watershed conditions – really matters, and affects the benefits a water reuse system may provide. In arid climates or areas with limited water sources, the water supply benefits of water reuse may be of highest importance. Near the coast, water reuse projects can be used to augment groundwater or wetlands as a way to prevent saline intrusion, protect water quality in estuaries, and provide water supply. For communities that span two river basins, water reuse can be a tool to manage flow and reduce interbasin transfers. And water reuse can even be used as a part of regulatory compliance strategy to meet targets on wastewater effluent discharge, nutrient loading limits, or other pollutant discharge limits. Thus, many of the main drivers for reuse are really tied to the water management needs for a utility.

There are a wide range of drivers and also hindrances that affect the analysis of costs and benefits, and ultimately, project implementation. But which drivers and hindrances are most influential across the country? Is overcoming the high initial capital costs the biggest barrier, or are others equally important? Does the rationale for investigating a water reuse project in the first place differ depending on where the utility is located?

The only way to find out is to ask… So we are.

A water reuse survey, supported by the Water Environment Research Foundation (WERF) and National Association of Clean Water Agencies, is investigating how the current drivers, hindrances, and partnerships that influence utilities’ decision making on water reuse projects vary across the country. This survey targets both utilities that have experience with water reuse, and those that have none. (Other experts and interested parties may answer as well). Upon completion of the survey, respondents will find instructions for how to be the first to receive summary survey results and notifications about publications related to the survey and the research project.

You can help in this effort by answering the survey, which we will hold open for readers of this blog through April 30th. Most respondents finish in about 15 minutes.

Click to Take the survey now! Or read more about the survey here.

For more information, please contact Lars Hanson at hansonl@cna.org.

Lars Hanson is a Research Analyst in the Energy, Water and Climate research group at CNA’s Institute for Public Research. CNA is a not-for-profit research and analysis organization located in Arlington, VA. The survey is a part of a WERF funded project titled “Economic Pathways and Partners for Water Reuse and Stormwater Harvesting.”

Leave a Reply