Every year, North Carolina coasts are a destination for tens of thousands of tourists and locals. But how often do visitors to NC’s beaches think about the strategies to keep beaches pristine? Every year, coastal erosion, a natural process exacerbated by factors like coastal development and climate change, eats away at the wide beaches that attract so many visitors.

What is Beach Nourishment?

Coastal erosion is the process by which local sea level rise, strong wave action, and coastal flooding wear down sands along the coast. Coastal communities adapt to these threats with shoreline stabilization measures. Shoreline stabilization is performed with the use of soft structures and hard structures. Historically, coastal municipalities have fought erosion with the use of hard structures. These solutions include rock, concrete, and steel to build sea walls, sills, and breakwaters. Soft structures are natural, and can include the use of fabrics, beach dewatering systems, sand bags, re-vegetation, and beach nourishment.

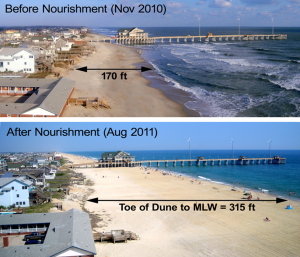

In 2003, the NC General Assembly banned hard structures in coastal erosion management, so the majority of coastal municipalities in North Carolina now rely on soft structures, specifically beach nourishment, to stabilize their shorelines. Beach nourishment is the process of adding large amounts of sand or sediment to the beach in order to resist erosion and increase the width of the beach. Sand is typically dredged from another location; usually, from the offshore portion of the site being nourished. Historically, beach nourishment projects have been performed on a town-by-town basis. Evidence suggests that towns tend to make isolated decisions about beach nourishment that do not account for their neighbors.

While beach nourishment offers shoreline stabilization benefits, it also provides recreational and economic benefits to coastal communities. A wider beach means more recreational space for beachgoers to enjoy, which brings more visitors to coastal communities, and allows more capital to flow into local economies. In addition, research suggests a wider beach increases ocean-front property values.

Cost of Beach Nourishment

The costs of beach nourishment, including planning, construction, and periodic maintenance, are primarily funded federally; the majority of funds coming from Federal Storm and Erosion, Federal Navigation, and Federal Emergency programs. The federal government has historically subsidized two-thirds of the total nourishment costs incurred by coastal communities. In recent years, however, some legislators have called for deep cuts in federal spending on nourishment or ending the subsidies outright. In response, the proportion of nourishment projects not involving federal funds has been increasing, and state-local and local-private funded nourishment projects have been on the rise [1].

In addition, projects funded by ACE are not spatially coordinated; individual communities make local decisions about beach nourishment without regard for the impacts on other communities. Actions of an individual community can cause damage to adjacent communities through spatial-dynamic feedbacks in the physical coastal system. For example, when communities are adjacent, the community with a wider beach loses sand to the community with a narrower beach [1].

As the climate changes, demand for nourishment funds is likely to grow, and an important question is raised – is the current approach to shoreline stabilization a viable long-term strategy?

Regionalization

One alternative to independent beach nourishment projects is a regionalized management strategy; multiple local government entities performing projects or programs together in order to combine resources and share results. Regionalized beach nourishment projects occur when adjacent communities employ beach nourishment projects at the same time, under the same management and contractors. There are significant ecological, economic, and recreational benefits from regionalized nourishment efforts, some of which are discussed below.

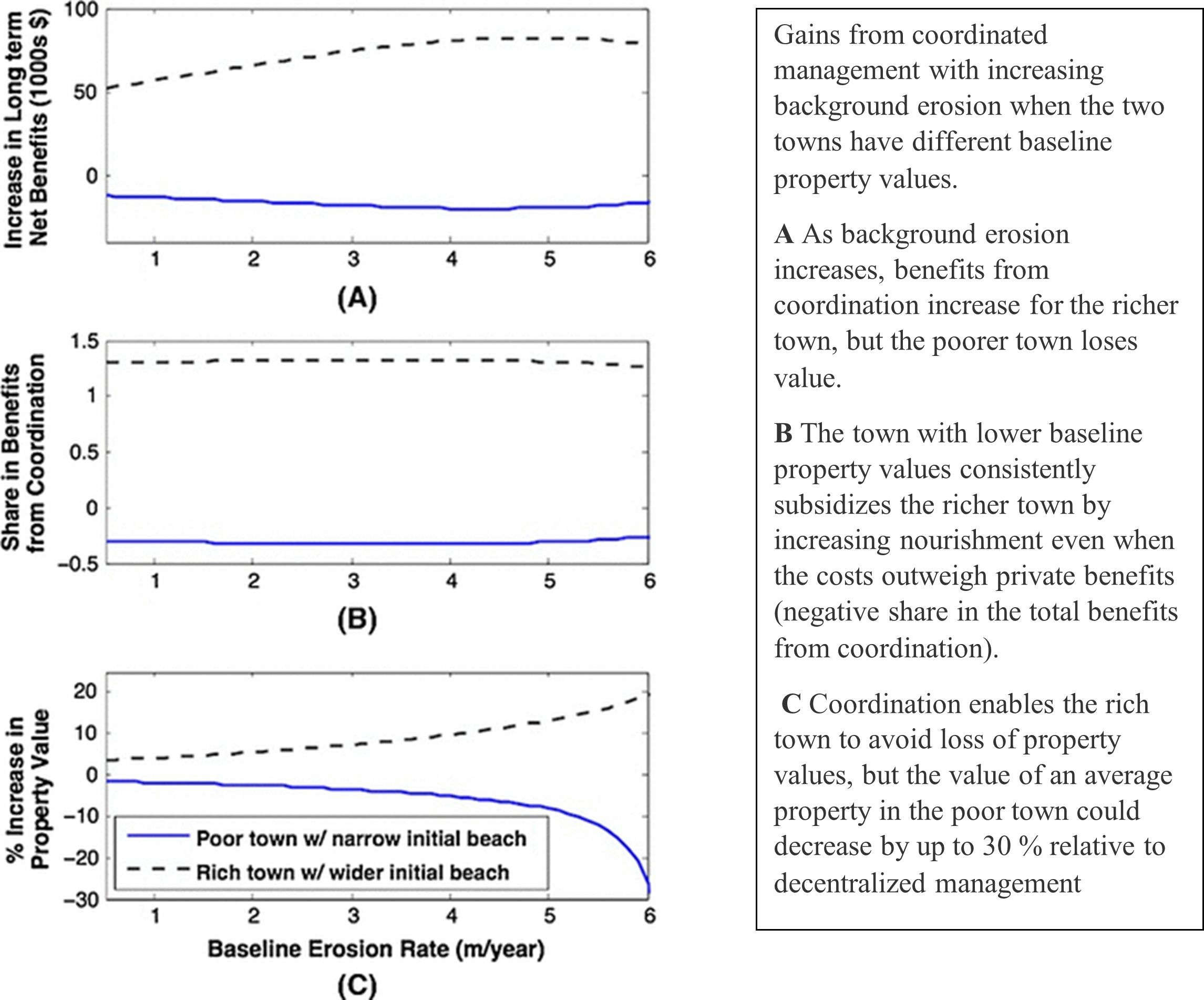

Coordination among coastal communities leads to wider beaches in participating communities, and decreases the difference in the beach width across communities [2]. According to research, nourishing beaches in tandem also reduces the effects of alongshore diffusion of sediment. Other research suggests that regional management strategies can slow the rate of fiscal resource depletion. In addition, the total amount of money spent on nourishment activities can decrease by as much as 25% when adjacent communities both conduct on-going nourishment projects, as opposed to the case where each community nourishes in isolation. There is also evidence that communities can better adapt to climate change by adopting a coordinated shoreline management strategy [2].

While the benefits of regional, coordinated coastal management strategies seem endless, it is important to consider any potential negative implications. Studies have shown that while there are net gains from coordination, and adjacent coordinating towns both benefit relative to sediment levels, wealthier towns tend to gain value, while poorer towns lose value. Greater costs are placed on the poorer communities, who have to bear the same costs as wealthier communities. As the benefits of coordination grow, these inequalities in outcomes will also grow [2].

Application in North Carolina

In North Carolina, two coastal counties have incorporated multiple towns into regionalized beach nourishment projects. In Dare County, the towns of Duck, Southern Shores, Kitty Hawk, and Kill Devil Hills employed a coordinated beach nourishment project in 2019, and plan to undergo a second project in 2022. Their regionalized effort is funded by a portion of Dare County’s 6% occupancy tax, property tax, and taxes from newly created municipal service districts. See this video for more information on Dare County’s regionalization project.

Carteret County employed the Bogue Banks Master Nourishment Plan in 2010, which is a comprehensive, regionalized, multiyear nourishment program. The program includes the towns of Pine Knoll Shores, Indian Beach, Salter Path, and Emerald Isle. Carteret County has received 50% of the required funding from the federal government, 25% from the state, and 25% from the county. The most recent funding project, in 2019, was financed by federal and state FEMA money, the county’s beach nourishment fund, and state money given to NC beaches to nourish after Hurricane Florence.

While there are no studies yet on the effectiveness of these regionalized efforts versus the individual efforts that came before them, the benefits of regionalized management are great, especially while neighboring towns are of similar fiscally. In the future, as climate change increases the frequency and intensity of storms, coastal towns can only benefit from regionalizing their efforts in order to make nourishment projects last longer, and require less capital.

Sources:

[1] Valverde, Hugo R., Arthur C. Trembanis, and Orrin H. Pilkey. “Summary of Beach Nourishment Episodes on the U.S. East Coast Barrier Islands.” Journal of Coastal Research 15, no. 4 (1999): 1100–1118.

[2] Gopalakrishnan, Sathya, Dylan Mcnamara, Martin D. Smith, and A. Brad Murray. “Decentralized Management Hinders Coastal Climate Adaptation: The Spatial-Dynamics of Beach Nourishment.” Environmental and Resource Economics 67, no. 4 (2016): 761–87.

Sarah Henshaw is a Graduate Research Assistant working on the Smart Management for Small Water Systems project at the EFC. Her work entails creating and updating funding tables that act as resources for local governments and other researchers across the country. She graduated from UNC Chapel Hill in 2020 with a degree in Environmental Studies and a minor in Marine Science and is currently a Masters in Public Administration student at UNC. She hopes to one day work in the public sector in non-profit management or in local government focusing on environmental policy – specifically marine conservation and protection.

Leave a Reply