Stacey Isaac Berahzer is a Senior Project Director for the Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina, and works from a satellite office in Georgia.

Stacey Isaac Berahzer is a Senior Project Director for the Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina, and works from a satellite office in Georgia.

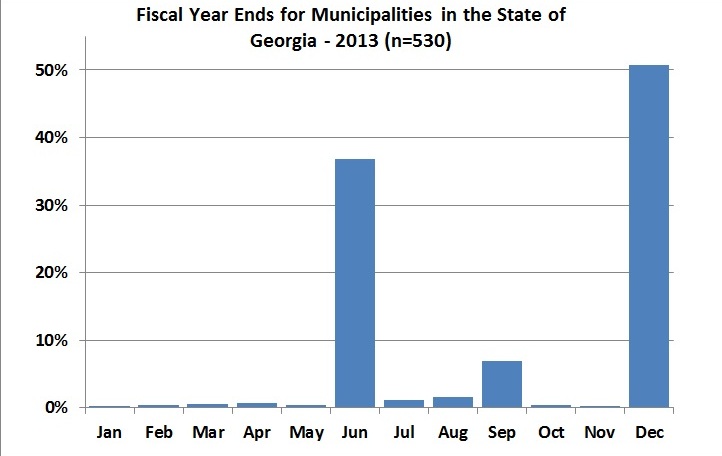

In each of the 12 months of the year, at least one local government in Georgia is ending its fiscal year. The chart below reflects the distribution of fiscal year ends (FYEs) for the 530 municipalities in the state. Some states stamp out this variety by handing down a fiscal calendar to local governments. But, the flexibility in Georgia perhaps speaks to the home rule nature of the state. The relevant Georgia statute says that when a local government is created, “The governing authority shall establish by ordinance, local law, or appropriate resolution a fiscal year for the operations of the local government.”

Since the local governments have control over the FYE, it can be assumed that each one has selected a date that has some advantage to the staff or the community involved. The eight (8) governments that end their fiscal year in August may have a busy summer, but they perhaps they want to be “ahead” of the start of the federal fiscal year in October. Apart from local preference, this staggered approach among the local governments may also have an advantage to some external entities such as third-party auditors. It seems that audit firms that serve local governments may have a more muted “busy season” since all of their clients aren’t reporting on the same schedule. But, might there be other entities for which this approach is less convenient?

This chart shows the month that the fiscal year ends for 530 municipalities in the state of Georgia

Informal conversations with some of the state’s funding programs for water/sewer/stormwater projects reveal that the staggering of these FYEs, if anything, has advantages to funders too. Funders have the benefit of parsing out their financial reviews over the course of the year. From a compliance perspective, this diversity may be a little less convenient though. For example, the Official Code of Georgia requires that the more than 530 cities and 159 counties submit audited financial statements to the Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts (State Auditor), provided that the population is greater than 1,500 or annual expenditures are more than $300,000, otherwise, biennial audits are acceptable. Confirming that this annual audit has been submitted within the 180 days allowed needs to begin with keeping track of when each local government’s year ends. (Monitoring compliance with this requirement is essential since the 50 local governments that were out of compliance in July 2013 are not eligible for state grant transmittals and may be required to return previously awarded grant funds.) However, beyond monitoring submission of these audits, the State Auditor is also required to review these financial statements to ensure compliance with generally accepted accounting principles, generally accepted government auditing standards, and federal and state regulations. Here again, the benefit of being able to parse these 700 reviews out over time may compensate for the compliance inconvenience of tracking FYEs.

This blog post is not advocating for standardizing the FYEs, but simply looking at the pros and cons. Maybe the factor that is most important in your opinion was omitted? Feel free to mention it as a “comment.” But, maybe the greatest disadvantage with this scenario is the inconvenience to the analyst trying to compile data and look for trends in local government financing over time.

Leave a Reply