by Jacob Mouw

This post was revised on September 25, 2014 to address nuances of water pricing and differences in conservation rates.

Drinking water, despite being a necessity, is relatively cheap in regards to its importance. At around $0.005 per gallon from the tap, it is astoundingly cheaper than, say, printer ink, which ranges from $13 to $75 per ounce, and yet is vastly more important. Despite this low price, water is a commodity, particularly in dry, drought-prone regions such as the southwestern United States. Utilities can deal with low water supplies by discouraging higher water use among customers through pricing. Having a “conservation rate” entails charging high enough prices for larger volumes of water use, therefore discouraging discretionary, non-essential use and promoting conservation. In the Environmental Finance Center’s recent Water and Wastewater Rates and Rate Structures Survey in the State of Arizona, thanks to funding from the Water Infrastructure Finance Authority of Arizona, we analyzed 355 water rate structures from 324 utilities.

Drinking water, despite being a necessity, is relatively cheap in regards to its importance. At around $0.005 per gallon from the tap, it is astoundingly cheaper than, say, printer ink, which ranges from $13 to $75 per ounce, and yet is vastly more important. Despite this low price, water is a commodity, particularly in dry, drought-prone regions such as the southwestern United States. Utilities can deal with low water supplies by discouraging higher water use among customers through pricing. Having a “conservation rate” entails charging high enough prices for larger volumes of water use, therefore discouraging discretionary, non-essential use and promoting conservation. In the Environmental Finance Center’s recent Water and Wastewater Rates and Rate Structures Survey in the State of Arizona, thanks to funding from the Water Infrastructure Finance Authority of Arizona, we analyzed 355 water rate structures from 324 utilities.

Conservation can be incentivized through price and non-price measures. Conservation pricing itself can be measured in many ways. One way that is easy to compute and compare between utilities is to calculate the water marginal price for use increasing from 10,000 gallons/month (above average residential water use in the State of Arizona) to 11,000 gallons/month. Among the 355 water rate structures in the survey, we observed quite a considerable range of conservation price signaling, as shown in the next graph. The minimum water marginal price, excluding wastewater, was $0 per thousand gallons. This was the case for five of the surveyed water rate structures, indicating that the water bill was priced using a flat monthly fee that does not take into account water use levels. In this type of rate structure, the residential customer has no price incentive to lower water use, since any increase in consumption is provided “for free” to the customer. On the opposite end of the spectrum, four utilities had water marginal prices that were at least $29 per thousand gallons. Residential customers at these utilities are highly incentivized to avoid increasing water use above 10,000 gallons in order to avoid having to pay at least $29 more in the next bill. More commonly, though, utilities in the State of Arizona charged a water marginal price between $1 and $4 for an increase of 1,000 gallons of water above 10,000 gallons. On the other hand, some utilities charge higher marginal prices and a few add wastewater rates on top of water rates, increasing the price signal that residential customers receive.  It is curious to note that water marginal prices among utilities in the Low and Mid Desert climate zone, where temperatures are the highest and precipitation the lowest on average, are on average 37% lower than in the rest of the state, even after controlling for the service populations of the utilities and ownership type and water source of the utility[1]. In other words, in the hottest and driest region of the state, the utilities are sending relatively weaker conservation price signals than in the other regions, as measured by the water marginal price at 10,000 gallons/month, irrespective of the water system size or ownership model or water source.

It is curious to note that water marginal prices among utilities in the Low and Mid Desert climate zone, where temperatures are the highest and precipitation the lowest on average, are on average 37% lower than in the rest of the state, even after controlling for the service populations of the utilities and ownership type and water source of the utility[1]. In other words, in the hottest and driest region of the state, the utilities are sending relatively weaker conservation price signals than in the other regions, as measured by the water marginal price at 10,000 gallons/month, irrespective of the water system size or ownership model or water source.

|

Climate Zone |

Number of Rate Structures | Water Marginal Price at 10,000 Gallons/Month | |

| Median($/1000 gallons) | Interquartile Range($/1000 gallons) | ||

| Cold Mountain/Cool Plateau | 80 | $3.83 | $2.47 – $6.22 |

| High Desert | 109 | $4.00 | $2.72 – $5.75 |

| Low and Mid Desert | 166 | $2.75 | $1.99 – $3.87 |

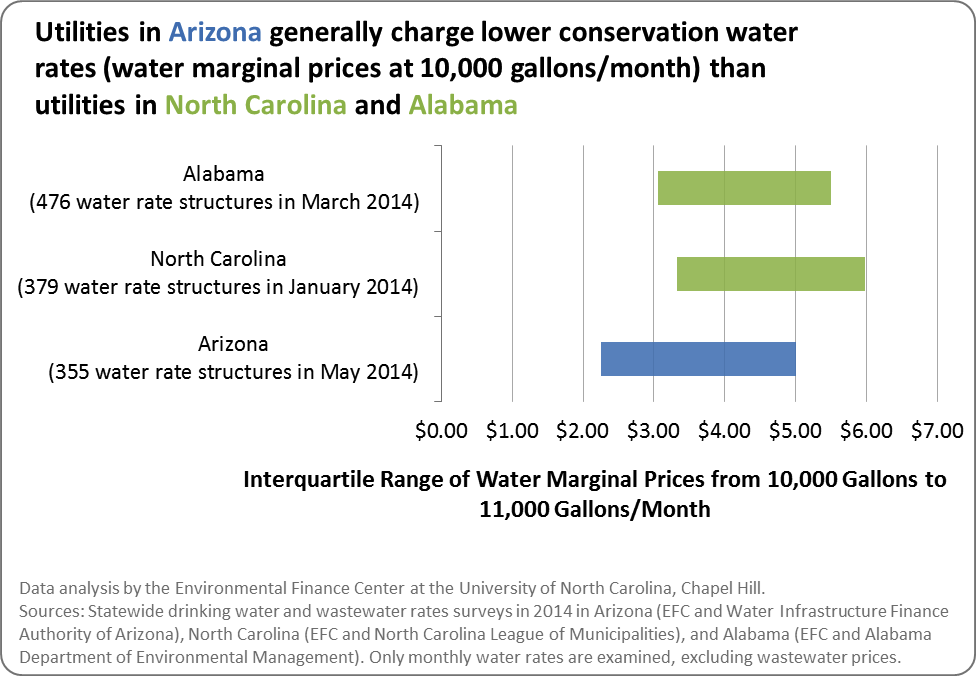

It is also informative to compare the water marginal prices charged in Arizona versus those charged in two states with generally wetter and cooler climates: North Carolina and Alabama. The conservation rates, as measured solely by the water marginal prices at 10,000 gallons/month, are generally lower in the State of Arizona than they are in the more water-rich States of North Carolina and Alabama. The median water marginal price in Arizona is $3.25 per thousand gallons above 10,000 gallons/month, compared to the median price of $4.32 per thousand gallons in North Carolina and $4.05 per thousand gallons in Alabama. Hence, by comparison, utilities in the drier-climate State of Arizona are not sending as strong a price signal as utilities in the other two states, where water prices are generally higher. There may be several reasons behind this fact which are not explainable purely from water rates data, such as different regional cost factors and differences in socioeconomics and policy environments of the different states.

Rate setting is a complex process that involves balancing many objectives in addition to promoting conservation. There are regional and local cost factors that add nuances to how much utilities can and do charge customers. Utilities that do not charge high rates may be promoting conservation through non-price methods, such as educational programs, outreach efforts, voluntary and mandatory restrictions on outdoor watering, etc. This blog post does not examine the issue of conservation beyond pricing or even rate setting in general. However, it is difficult to escape the impact of pricing signals which, in some cases, may interact with other conservation measures in ways that are difficult to predict.

To examine each utility’s water conservation price signal in the State of Arizona, and for more information about rates, affordability and financial performance of the utilities in Arizona, please use the recently-released, interactive Arizona Water and Wastewater Rates Dashboard, download tables of rates and rate structure details for all utilities, or read the report summarizing the rates and rate structures used across the State of Arizona (coming soon here). The Rates Dashboard, updated in September 2014, is much improved from the version created last year, with additional benchmarking metrics and a much larger sample of utilities included. To learn about the dashboard and how to use it in assessing an Arizona utility’s rates, financial performance, affordability and conservation price signaling, please view this video recording and archived slides.

[1] This result is statistically significant, controlling for the service populations, the ownership structure of the utilities (for-profit versus local government/not-for-profit), and water source (groundwater versus surface water/purchase water). Regression results are available upon request; please contact Shadi Eskaf.

[1] This result is statistically significant, controlling for the service populations, the ownership structure of the utilities (for-profit versus local government/not-for-profit), and water source (groundwater versus surface water/purchase water). Regression results are available upon request; please contact Shadi Eskaf.

Jacob Mouw was a Rates Survey Analyst at the Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill from 2013 to 2014. He recently graduated from UNC with Bachelor’s degree in Environmental Sciences. Edits provided by Shadi Eskaf and David Tucker.

This post is a product of the Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Findings, interpretations, and conclusions included in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of EFC funders, the University of North Carolina, the School of Government, or those who provided review.

Metered tap water as sold in the US is sold for less than the actual cost to deliver it on a sustainable basis. This mis management or poor leadership of water districts has caused the current state of disrepair. Monies collected for water have been mismanaged or the pipes today would have been managed correctly and a small but steady repair would be all that is needed. Growth has been steady and predictable, bonds were not passed because people were not educated and therefore voted to not pass bonds to upgrade aging pipes and systems. If not bonds, the districts could have saved up money instead of squandering it. If not squandered, then they did not charge enough, as I said in my first line. Point is, leadership needs changing, prices need to rise to the actual cost of sustainably providing water. This is simple, one can not eat its cake and have it too. Or consume/waste its water and have it too. Prices in past have allowed waste, plain and simple. Do we need to pass laws prohibiting people from throwing money all over the streets and down toilets?, no. We are too smart to throw away money and since water does not cost very much, we throw it away.

Jacob,

I enjoyed reading your article. I have two points I want to share with you about the price of water in Arizona. First, the water resource portfolio for Flagstaff and other areas in the northern part of the state are shallow and lack diversity. Second, revenue from hydro electric power generation subsidizes the cost of water services. Electric power is the silent partner of the water industry in Arizona.

William