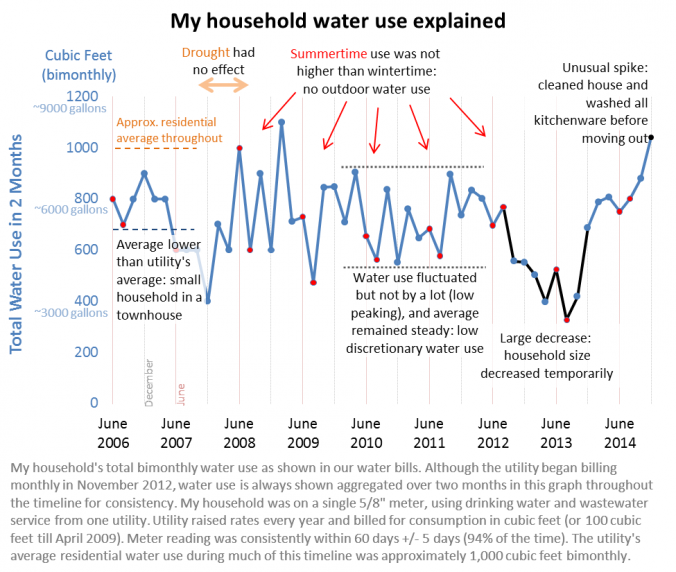

Last week, I posted a graph of my household water use for the past few years and challenged our readers to identify as many interesting characteristics about my household as they can. Often, the only data a water utility has on their customers are what they have in their billing records. Other household characteristics, such as size of household, income, age, house and lot size and features, water use behavior and preferences, etc., are very difficult to obtain for each customer. However, as demonstrated by my own personal example, mining the billing data alone can reveal much about each household. Here is what my water use history reveals about my household, and the application of this exercise in water resources and utility finance management.

Thank you to everyone that accepted the challenge and provided thoughts about my household water use. Many guesses were quite accurate. Here is what the reality was:

- My household size is small (two people) and we lived in a small townhouse. This can be revealed by our much lower than average water use. On average, our household only used about 70% of the water levels that the average residential customer in our city uses. Even our peak usage barely reached the average residential water use level.

- Our outdoor water use is negligible. We don’t have an irrigation system or a swimming pool, we don’t water lawns or gardens, and we don’t wash our cars every week in the summer. This is clear because our summertime water use did not increase significantly over our wintertime water use. Our water use peaked in winter and fall months more often than in summer months. Another hint to the utility would be the fact that we don’t have a separate meter for an irrigation system, but the absence of a separate meter does not always indicate that a household is not a significant irrigator.

- We had frequent but temporary changes to our weekly routines that affected our water use, as shown by alternating peaks and valleys every couple of months. My wife and I attribute this to frequent traveling, mostly for work, and perhaps because we don’t use the washer and dishwasher on a set weekly schedule.

- There was a significant and more long-term change to our household at least once in this period. Some hypothesized that we had a baby or a person moved in at the beginning of 2014 because water use increased substantially then, but that was not true. In actuality, due to a typical modern life career situation, one of us moved out of state for more than a year around 2013, effectively halving our household and water use in North Carolina, and then returned at the beginning of 2014.

- We may not have much discretionary water use that we can cut back. In most calendar years, our maximum demand was less than twice our minimum demand (our average yearly peaking ratio was 1.8). In other words, we didn’t vary our water use much within a year and we hovered around our already-low average water use. In fact, over the eight and a half years, our average water use remained relatively steady, despite consistently rising rates and a general trend in North Carolina households to decrease water use over time.

- Our household was not very responsive to rate increases and mandatory watering restrictions. Our water use did not decrease during the drought period in 2007-2008, and even though the utility raised rates every year and switched to increasing block rates midway through this timeline, our average water use remained relatively steady. This can be explained by the points made above: we don’t use water outdoors (so mandatory restrictions had no effect on us), and we are already relatively efficient in our indoor water use without much discretionary water that we could cut back in response to drought or price. If rates were much higher than they were, we may have invested in more efficient appliances and lowered our baseline demand, but that was not a cost-effective option for us during those years.

As demonstrated, the utility could use my water use records from its billing system to understand what kind of household ours was, at least as it relates to water use. It might be difficult still to guess the exact context in great detail, but our water use records could at least provide a broad overview of our household: we are a low water-using, small household, with no outdoor water use and little discretionary indoor water use.

More important than understanding what type of household we are, though, is better understanding how the utility’s rates and practices affect our household, and how to effectively communicate with us. Switching to increasing block rates or raising rates at the higher blocks had and would have no effect on our water use or bills, because we simply don’t use that much water. During a drought, instead of mailing us notices about mandatory restrictions and pamphlets about general ways to reduce water use, a more effective communication strategy would be to tailor the message about how best to reduce indoor water use and the benefits of investing in more efficient appliances (since our household water use was already mostly non-discretionary). In fact, given that our household’s water use is already very low and with low risk of demand peaking during a drought year, the utility might wish to skip sending us any communication about water efficiency, choosing to spend that money instead in communicating more with households that exhibit high discretionary or outdoor water use.

The power of this exercise is best fulfilled when a utility is able to analyze the water use histories of each and every one of its residential customers (and non-residential, as my colleague blogged about recently). Imagine what could happen if a utility is able to generate a broad understanding of each of its household’s water use behavior. Instead of assuming that “average residential customer” is a surrogate for all residential customers (which is commonly practiced by only analyzing average use and average bills across the entire customer base for certain months or years), the utility will be able to identify different groups of households that have unique water use behaviors, as shown in the image below. With groups of residential customers now distinguished, the utility can assess the effects of its rates and practices on unique groups of customers and better predict their effects on water demand and revenues. Moreover, the utility could implement a tailored communication strategy to different groups of customers instead of blanketing the customer base with a message that might only resonate with a portion of customers. These ideas are described in a guidance document published by AWWA for water utility managers in 2013, titled “A Guide to Customer Water-Use Indicators for Conservation and Financial Planning” (download a free copy here).

Image for “A Guide to Customer Water-Use Indicators for Conservation and Financial Planning.” Copyright (c) American Water Works Association, Amy Vickers & Associates Inc., Mary Wyatt Tiger and Shadi Eskaf.

Applying this method to all customers does not mean that a staff member will need to pull out each customer’s water use records, create a graph and assess them individually for all customers. The EFC developed and described in a 2011 Journal AWWA article (“Mining Water Billing Data to Inform Policy and Communication Strategies“) a method that any utility or its consultants can apply to quickly dig through its billing records using an algorithm to generate groups of residential customers based on water use behaviors, without having to manually analyze each customer’s records individually. We applied this methodology to analyze billing records for several large urban utilities, created customer profiles and discussed with utility managers how customer base segmentation can help their pricing, communication and water resource management strategies.

Leave a Reply