Guest post by Maddie Atkins

Water and wastewater infrastructure needs in the US continue to grow. The EPA Drinking Water Needs Survey and Clean Watershed Needs Survey estimate that a combined $655 billion in water and wastewater infrastructure investment is needed nationwide over the next 20 years. In North Carolina over the next 20 years, estimates of water system capital costs range between $10 and $15 billion, and wastewater system needs range from $7 to $11 billion. As utilities raise capital to make infrastructure improvements, most turn to debt as an instrument to fund projects. As of the end of fiscal year 2017, local government utilities in North Carolina have $8.3 billion in outstanding water and wastewater debt.

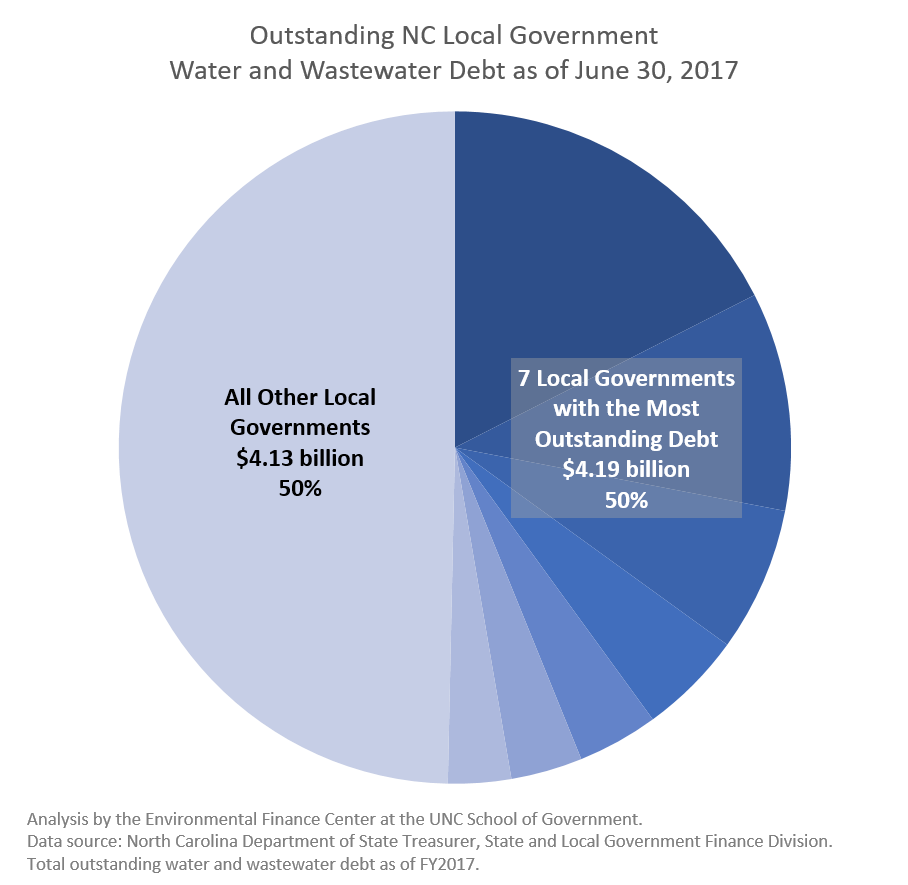

Of the total $8.3 billion in outstanding debt, half is held by only 7 utilities. Although only a select few utilities carry a sizeable portion of the total outstanding debt, they are typically able to spread their debt over a larger service population. Combined these utilities serve 2.65 million people, 26% of the state’s total population.

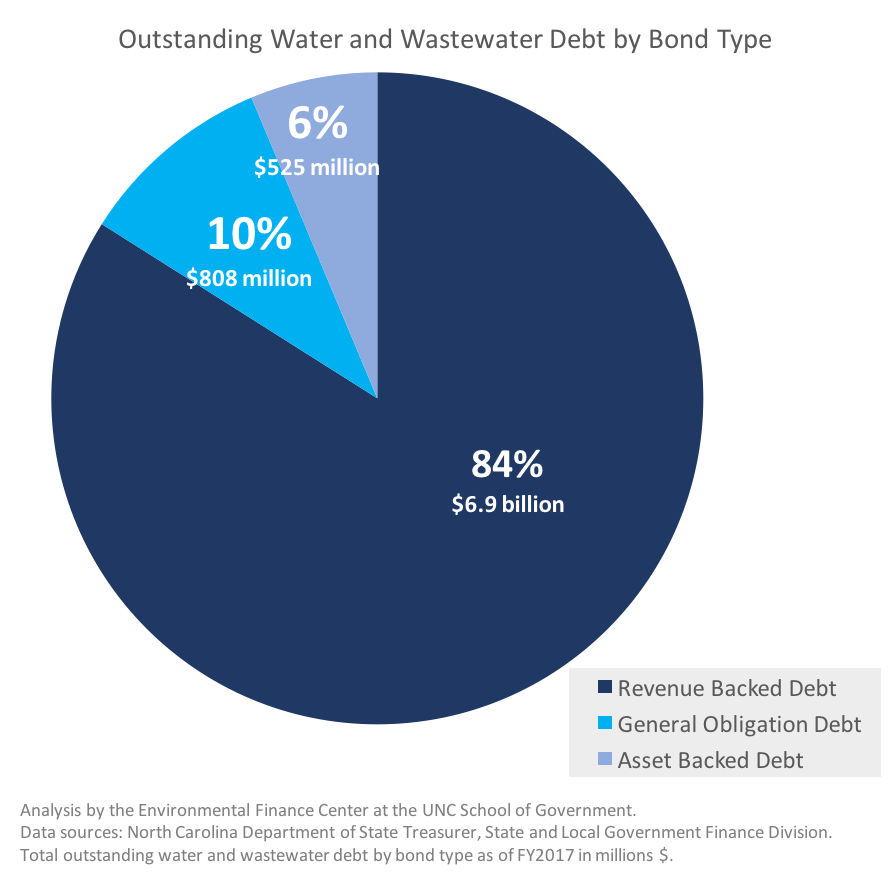

Current outstanding local government water debt is comprised of different types of bonds and loans backed by different types of security. Revenue backed bonds, municipal bonds that are backed by utility revenues made by rate-payers, make up the vast majority of outstanding debt (84%). Once-popular general obligation bonds, which are backed by credit and various taxes, make up only 10%. Asset backed debt, installment purchase loans that are backed by the utility assets, account for a sizeable portion (6%).

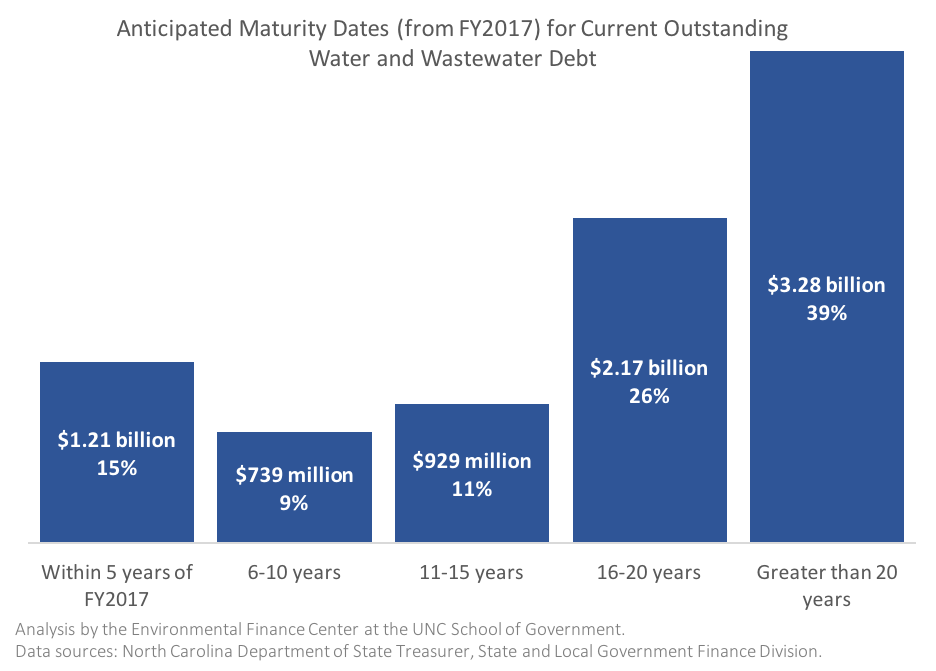

Knowing when this debt comes off the books has important financial implications for utilities across North Carolina. As debt is paid off, a utility may be able to redirect revenue that had been used for those associated debt service payments to investment in other projects. Of the current $8.3 billion outstanding water and wastewater debt, 15% of that has a maturity date within 5 years of fiscal year 2017. However, the majority of current outstanding debt has a maturity date within 16-20 years (26%) or greater than 20 years from FY2017 (39%).

The EFC is working with the North Carolina Division of Water Infrastructure to better understand water, wastewater, and stormwater finance practices and to develop funding programs and strategies that support local efforts to improve water management. This post is the first in a series describing the state of water debt in North Carolina.

Maddie Atkins is pursuing a Master of Environmental Management at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment, where she is focusing on urban water management and planning. As a research assistant for the EFC at UNC, her work focuses on characterizing the debt that water utilities in North Carolina take on to finance projects. Maddie holds bachelor degrees in Environmental Geology and Environmental Studies from Case Western Reserve University.

I was wondering if you have access to similar data and analysis, such as the one that you developed, for other states. I am currently work live in Vermont, but work in water and wastewater project in the states of Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island, so I am curious about what the situation might in those states.