The current housing market boom leads to large tracts of available land being swept up into the hands of private developers. For many local governments, development is good. It provides access to new tax revenues and tends to perpetuate growth; an area actively developing tends to attract more industries and people. These new revenues can be used for any number of purposes, including adding services, such as land conservation or parks and recreation, to the municipality. The challenge is in protecting land before it falls into the hands of developers, and balancing the open space needs of the municipality and its constituents with the municipal revenue streams.

Any land conserved or turned into a public park is lost property tax revenue. In larger cities with combined sewer systems, land conservation may have a direct return on investment, whereby the open spaces reduce the total impervious surface and associated runoff, and thus prevent or reduce combined sewer overflows. But in municipalities without regulatory drivers, the benefits may be less direct and harder to quantify. Green space does provide many direct and indirect economic benefits to a municipality, including attracting development and increasing property values. Other, less measurable benefits include mental, physical, and emotional wellbeing, which are important to overall quality of life but do not have a market value. In a Benefit Cost Analysis, these values are important, but challenging to meld with dollar values for costs or dollar value benefits in avoided costs for upsizing a stormwater system.

Nevertheless, the benefits exist and there are many cases where local governments elect to conserve land within its jurisdiction. Funding land conservation can include many sources, including local budgets, bonds, grants, or partnership funding. However, according to a guide from the Trust for Public Land, the most reliable option is one that is not dependent on outside funding sources or subject to budget fluctuations. While there are some cases where municipalities acquire land within the annual budget expenses, these are usually emergency acquisitions and tend to have very specific drivers.

That leaves voter referendums for land conservation and parks and open space. These voter referendums allow the electorate to have a say in the decision-making process. In some cases, they are required by state statute. For example, in North Carolina, if a local government is to pledge its taxing authority to issue general obligation bonds for land conservation, it is required to hold a referendum. The public votes, and if the electorate is supportive, local governments are able to access large amounts of capital at very low interest rates. It just requires a majority vote. Easy, right?

In many cases, yes. Voter referendums tend to be wildly successful, winning far more often than they fail. But, according to Banzhaf, Oates, and Sanchirico (2010), this outcome may simply reflect good strategy. Local governments tend to do their research before putting refereda to a vote. Therefore, only supported referenda actually make it on the ballot, driving up their success rate.

Land Conservation Ballot Measures in the US

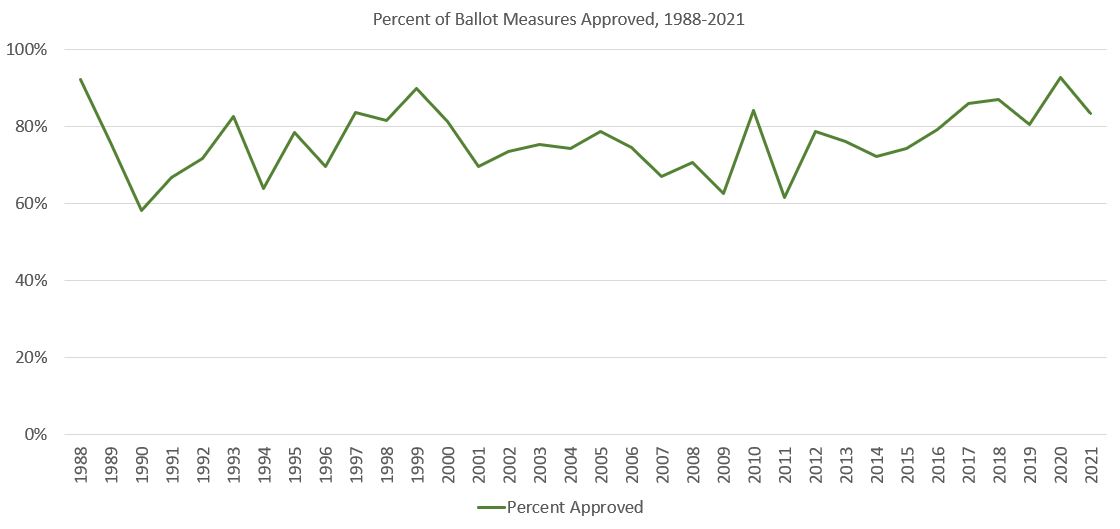

The Trust for Public Land has been collecting data on land conservation voter referenda since 1988, compiling it in their landvote database. Since 1988, 76% of ballot measures that included conservation have been approved, equating to $82 Billion in conservation funds. The success has remained relatively stable through time, as illustrated by the graph below.

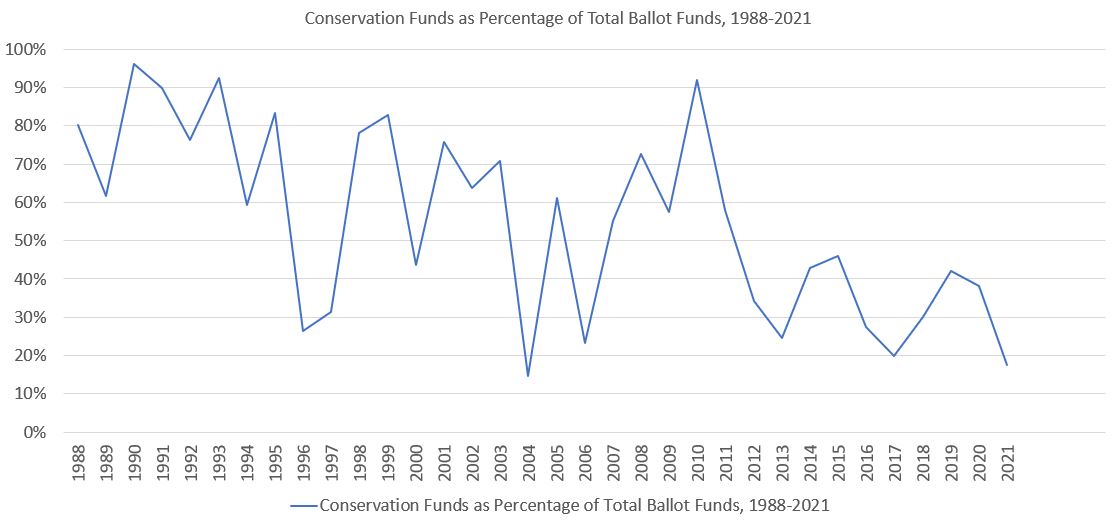

In contrast, the percentage of the total ballot measure funds associated with conservation has declined over time. This is not to say that total conservation funds have declined, but rather suggests that local governments are rolling many capital expenses into a single ballot measure, thus making the total bond issuance greater even at the same level of conservation spending. The figure below illustrates conservation’s share of total funds over time.

Ballot measures remain a very popular form of funding land conservation in the US, and in the absence of a new mechanism, will likely continue to be the primary mechanism for land acquisition by local governments. Again, the decline in the percent of total ballot funds does not necessarily reflect a decline in the total conservation funding over time. Indeed, these numbers tend to fluctuate year to year and do not illustrate a clear trend.

Conservation Funding in NC

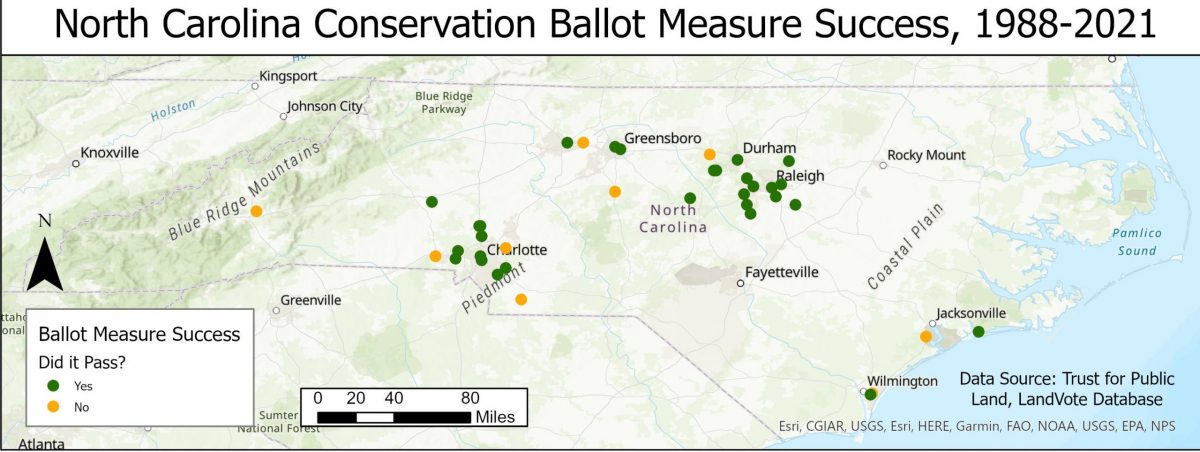

Trust for Public Land’s LandVote Database also provides state level data on ballot measures. This includes the name of the jurisdiction, the type of financing mechanism, the date of the ballot measure, the conservation funds, the success (pass/fail), and the associated yes votes versus no votes. With an 81.7% success rate in NC, these ballot measures have led to over $815 million of a proposed $1.1 billion in conservation funding since 1988. Interestingly, from 1988 to 2018, all but one proposed conservation measure relied on financing through a bond. In 2004, Guilford County proposed a conservation ballot measure paid for by property tax, but it did not pass. Since 2019, two of the three conservation based ballot measures proposed being financed using a sales tax. Of these, only one passed (Chatham County). The map below shows the distribution of ballot measures by success across NC.

What does it all mean?

The results suggest that conservation based ballot measures are very successful. This does not mean that voters are overwhelmingly in favor of land conservation, but rather means that only those ballot measures with community support actually make the ballot. Further, the recent moves towards sales tax backed conservation funding is something to watch. As tax-strapped municipalities experience rampant growth and development, finding more politically feasible ways to finance conservation will become even more important. In South Carolina, the use of sales tax backed finance has been implemented since 1988, and six of the nineteen SC conservation ballot measures recorded in the LandVote database have used sales tax to finance the conservation.

While land conservation finance may not always be the most exciting topic in the world of environmental finance, it remains a vital part of ensuring open space provision, quality of life, and wellbeing of city-dwellers, especially as urban hubs continue to urbanize.

Want to learn more about launching a successful ballot measure? Check out the Trust for Public Land’s Guide for Designing Winning Conservation Finance Ballot Measures.

Austin Thompson joined the EFC at UNC in 2018 as a Project Director. In this role, she conducts applied research and provides technical assistance and training for environmental service providers. Thompson holds a BS in Biological Sciences from the University of South Carolina and a Master’s of Environmental Management from Duke University, with a concentration in Environmental Economics and Policy. She is currently pursuing a PhD at NC State University, while continuing to work at the EFC conducting applied research.

Leave a Reply